MONI GARCIA / MÁSCARA CONTRA MÁSCARA: 4 POEMS

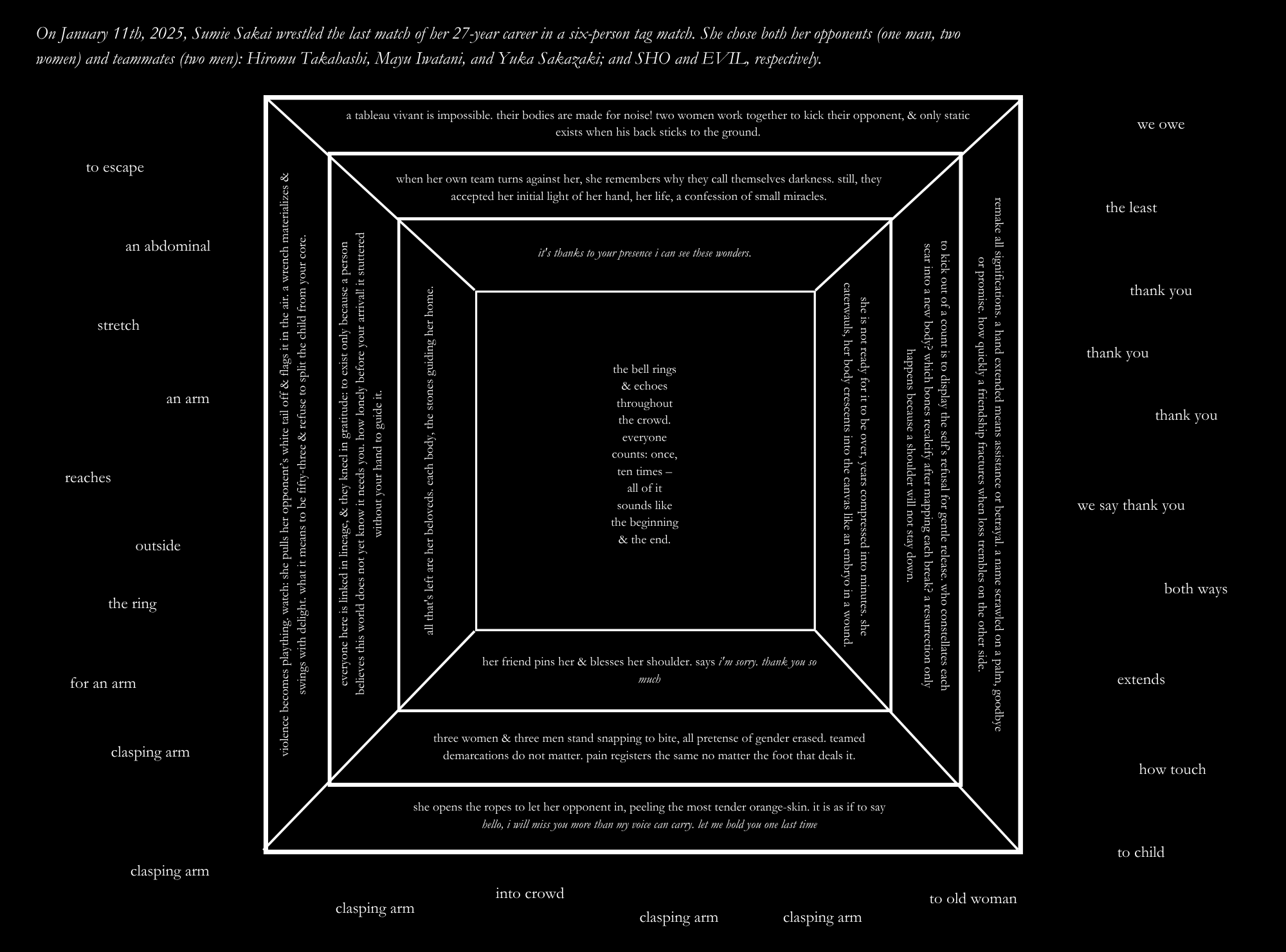

I Watch Sumie Sakai’s Retirement Match

Máscara contra máscara

my entrance astounds.

when I preen into the pulse of night

thousands of hands refract chorus of movement

for the window I’ve invited

them to gather their looking.

the colors I declare:

stain-glass mountained sunrise the dappled

light that plays on a river –

all sewn with my symbol of choice.

to obscure my face I reveal

the eaves of desire that slope from me.

become the favorite version of living

where days do not begin

& end with treading water

my trachea’s scales measure each languid hour;

shape of my outline demarcated

by a ruler’s notches to align

hairs down its divots.

when I step forward tilt my head back

a new birdsong enters

to flock between ribs.

in matches the faces we wager

must prove this science of survival.

ponds of sweat diagramming edges

of lycra amassed for each little war

I refuse towards ruin.

each mask captured I swallow.

imagine: your decapitation.

imagine: the imperfect slit your neck makes.

who will I become tonight?

which sound will tremble

into a newer body?

there are times when loss

has idled too close to me.

scraped its nails in the air

between us. I watch catastrophe

drawn out by my hands from a man.

see them get down on two knees

& angle their head parallel

to the ground that betrayed them;

waves of grief they shoulder unendurable.

I hold their mask grip memory

until I feel it as my own.

here is a rebirth & the self

cleaves to move through it.

They’re Called the Golden Lovers

After an especially grueling first match, Kenny Omega and Kota Ibushi decided they did not want to wrestle against each other, but wrestle together. While the company pitched they call themselves “The Golden Brothers”, Omega and Ibushi chose the tag team name “The Golden☆Lovers”.

& it’s unfathomable how often a hand’s devotion

is mistaken for distance.

that to press a mouth to

hollow of wrist

is being too read into–

actually it’s more like

they’re best friends did you know they train together

but they’re just super close.

is it friendly that Omega first saw Ibushi

draped behind screen & fissures

& couldn’t imagine the movement of breath

without this man's fingers to guide it?

life is not worth the light it daily spills

unless he could feel him

unstoppable mountain & feverish

against him.

this is not to deride the power of friendship

despite the cliché

but why is it offered

as a way out against

the very real existence

of a man fucking a man

everyone’s already watching

two men grip each other in front of swarms

of eyes lie back in a ring

what’s one step further

what does a man contorted with grief

unable to bridge the length of his longing

to his beloved look like to you

to glance upward & see him through

the dapple five fingers make.

but it doesn’t matter

how others un-name them

try to rip the seams

threaded to their bodies.

everyone replays the scene

where they hold each other

in the center of an arena

two weeping loons breathless

against their lover’s neck

the type of relief that comes

only after tilted years of absence.

want is the balcony they leap off of

all for the brief moment for a fall

to become a closeness to God.

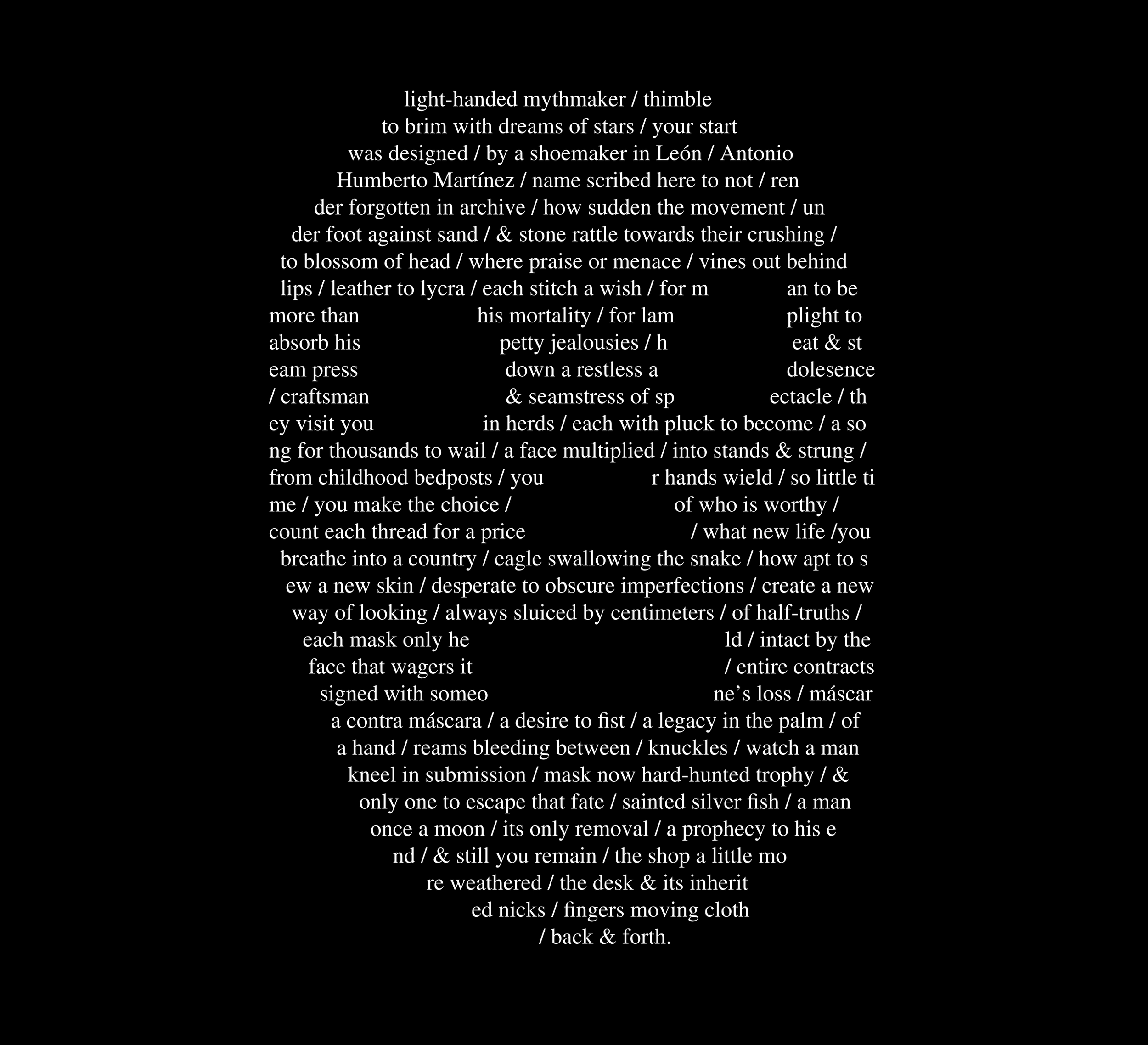

Ode to Mascareres

Moni Garcia is a queer Latine artist and poet from Illinois. They have been published in Poetry Online, Foglifter Journal, NOTHING HERE IS CORRECT AND IT IS DELICIOUS, a zine of writing and art in dedication to the CW television network, ALOCASIA Magazine, and elsewhere. They call on you to recommit yourself to the liberation of Palestinian people every day.